By Wassem Amin, Esq., M.B.A.

Over the past couple of years, the use of EB-5 Regional Centers by project developers to raise capital has been increasing in popularity. A designation as a Regional Center by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”) allows a project developer, or an entity on behalf of a project developer, to raise capital from foreign investors seeking an EB-5 Immigrant Investor Visa.

The increased interest in EB-5 investments has been attributed to a combination of factors including: (1) the overhaul of the program by USCIS and the creation of a dedicated EB-5 adjudication department; (2) the decrease in domestic investment capital after the 2008 recession; and (3) the increased political instability in foreign countries leading many high-net worth immigrants to relocate to the United States.

Utilizing Regional Centers as a source of funding for project developments is an attractive option due to the typically low cost of capital to the developer as well as the ability to generate a profitable revenue stream from administrative fees charged to the immigrant investors. In addition, administrative fees generated from a Regional Center typically offset the up-front costs involved.

Investing through a Regional Center is attractive for foreign investors because the investment is usually held in an irrevocable escrow account pending the approval of their initial application with USCIS (Form I-526). Upon the approval of the I-526 Application, the funds are released to the developer and the investor is issued conditional permanent residency. This ensures that, in the unlikely event the foreign investor is denied by USCIS, they are refunded their investment. As an additional layer of protection, a comprehensive questionnaire is typically used to qualify the foreign investor and determine their eligibility beforehand. That way, the Regional Center would be able to suggest alternative investments to potential foreign investors who may not be approved by USCIS.

What are Regional Centers?

USCIS defines a Regional Center as “any economic entity, public or private, which is involved in the promotion of economic growth, improved regional productivity, job creation and increased domestic capital investment.” A Regional Center could be independent of the actual project or created in connection with a specific development. Regional Centers are set up to act as intermediaries between foreign investors and EB-5 eligible projects in the United States. To apply for Regional Center designation, a Form I-924 is submitted to USCIS, and processing times are between 4-8 months.

A range of different real estate projects have qualified for regional center status, including shopping malls, hotels, mixed use developments, warehouse distribution centers, manufacturing facilities, and business incubators. Because the key thrust of the Regional Centers is to create jobs, many regional centers are sponsored by or work extensively with local governments in a form of public-private partnership, but this is not a requirement.

In order to obtain approval from USCIS for designation as a Regional Center, the entity has to submit a proposal which must:

- Clearly describe how the center focuses on a geographic regions of the United states and how it will promote economic growth through improved regional productivity, job creation, and increased domestic capital investment;

- Provide in verifiable detail how jobs will be created indirectly;

- Provide a detailed statement regarding the amount and source of capital which has been committed to the Regional Center, as well as a description of the promotional efforts taken and planned by the sponsors of the Regional Center;

- Contain a detailed analysis regarding the manner in which the center will have a positive impact on the regional or national economy in general, as reflected by such factors as increased household earnings, greater demand for business services, utilities, maintenance and repair, and construction both within and without the Regional Center; and

- Be supported by economically or statistically valid forecasting tools, including, but not limited to, feasibility studies, analyses of foreign and domestic market for the goods or services to be exported, and/or multiplier tables.

The Job Creation Requirement

The EB-5 visa has two different minimum investment requirements, depending on whether the geographic location of the investment is a Targeted Employment Area (“TEA”). A TEA is an area that is in a rural location (as determined by each specific state) or an area with an unemployment rate of at least 150% of the national average. If the investment is in a TEA, the minimum amount per each immigrant investor is $500,000.00. If it is not in a TEA, then the minimum amount is $1,000,000.00.

Each foreign investor must demonstrate that their investment has created (or will create within two years) a minimum of 10 full-time jobs for U.S. persons (a permanent resident or a citizen). This requirement is the same whether the investment is within or outside of a TEA—i.e., whether the investment is $500,000 or $1,000,000. However, if the investment is through a Regional Center, indirect (and induced) jobs may be counted.

To establish that 10 or more indirect or direct jobs will be created by the business, USCIS rules provide that indirect methodologies may be used, which may include multiplier tables, feasibility studies, analyses of foreign and domestic markets for the goods or services to be exported, and other economically or statistically valid forecasting devices which indicate the likelihood that the business will result in increased employment.

For example, if a multitenant shopping center is designated as a regional center, the full-time jobs created by the ownership and management of the shopping center are directly created jobs. The jobs created by the tenants of the shopping center are indirect jobs. There may be 5 or 10 full-time positions created by operating a property management office, but the jobs created by the tenants of the shopping center could be over 100, and those jobs would all be counted to satisfy the job creation requirement. For these reasons, in a regional center, it is much easier for the investor to meet the employment requirements. Further, if more jobs are counted in the business, more EB-5 investors can participate in the project, resulting in more funding for the developer.

Structuring the Regional Center: Investment Models and Exit Strategies

The creation and management of a Regional Center will require expertise in the following areas: (1) EB-5 process; (2) immigration law; (3) equity fund structuring; (4) transaction due diligence and structuring; (5) economic analysis; and (6) marketing. Dhar Law LLP is able to assist with all of the above—except the marketing. In addition, while the economic analysis will be conducted under our supervision, it will be primarily done by an economist within our network who specializes in EB-5 Regional Centers. An additional requirement is having access to pipeline of foreign investors sufficient to meet the capital requirements of the project.

As for the investment models, EB-5 investments are generally one of two high-level models: an Equity Model or a Debt Model. In the Equity Model, the investor acquires an ownership interest in the development project, entering as limited partner. This is a well-established model with a track record of USCIS approvals and is currently the primary strategy for EB-5 investments. At the end of the specified term (generally five years, but could be less), the EB-5 investor’s interest in the project is sold to other interested parties. The proceeds from the sale are returned to the investor. Complications could arise in the sale of the equity, so the return of investments is not guaranteed.

In the Debt Model, the investor also joins as a limited partner, but provides a low-interest term loan to the project developer rather than acquiring a stake in the project. Repayment of the principal is made either through sale of the project or refinancing of the EB-5 loan at the end of the term (also generally five years). This model, while it has received approvals from USCIS, is still fairly new and may undergo greater scrutiny. The issue is whether Debt Model projects guarantee repayment to the investor—which is not allowed under EB-5 regulations because the invested capital must be “at risk.”

For example, if a new commercial enterprise’s limited partnership (LP) agreement contains a buy-back agreement (i.e. a redemption clause guaranteeing the return of the investor’s capital investment), then the investor’s capital investment will not be a qualifying “at-risk” investment for EB-5 purposes. Likewise, if the LP agreement requires the payment of fees from the investor’s capital investment to the extent that the investment will be eroded below the qualifying level, preventing the full infusion of the capital into the job creating enterprise, then the investor’s capital investment will not meet the required EB-5 level of investment.

Initial Evidence and Documents Required by USCIS

- Location of Regional Center: The Regional Center must focus on a specific geographical area. This area must be contiguous and clearly identified in the application by providing a detailed map of the proposed geographic area of the Regional Center.

- Creation of Jobs: Each Regional Center must fully explain how at least 10 new full-time jobs will be created by each individual alien investor within the Regional Center either directly or indirectly. The applicant must provide an economic analysis that relies on statistically valid forecasting tools that shows and describes how jobs will be created for each industrial category of economic activity. The job creation analysis for each economic activity must be supported by a copy of a business plan for an actual or exemplar capital investment project for that category.

- Business Plan: A business plan provided in support of a regional center application should contain sufficient detail to provide valid and reasoned inputs into the economic forecasting tools and must demonstrate that the proposed project is feasible under current market and economic conditions. The form of the EB-5 investment from the commercial enterprise into the job-creating project (equity, debt, etc.) should be identified. The business plan should also identify any and all fees, profits, surcharges, or other similar remittances that will be paid to the regional center or any of its principals or agents through EB-5 capital investment activities.

- Infusion of Capital: The application must be supported by a statement from the principal of the Regional Center that explains the methodologies that the Regional Center will use to track the infusion of each EB-5 alien investor’s capital into the job-creating enterprise, and to allocate the jobs created through the EB-5 investments in the job creating enterprise to each associated alien investor. The anticipated minimum capital investment threshold (either $1,000,000 or $500,000) for each investor must also be identified.

- Operational Plan: The application must be supported by a detailed description of the past, present and future promotional activities for the Regional Center. It must include a description of the budget for this activity, along with evidence of funds committed to the Regional Center for promotional activities. The plan of operation must also address how investors will be recruited and how the Regional Center will conduct its due diligence to ensure that all immigrant investor funds affiliated with its capital investment projects will be obtained from lawful sources.

- Prospective Economic Impact: The application must be supported by a general prediction of the prospective impact of the capital investment projects sponsored by the Regional Center, regionally or nationally, with respect to increases in household earnings, greater demand for business services, utilities, maintenance and repair; and construction both within and outside the Regional Center.

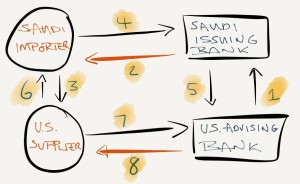

- Organizational Structure: The application must fully describe and document the organizational structure of the regional center. In addition, it should be accompanied by the capital investment offering documents, business structure, and operating agreements of the proposed commercial enterprise that will be affiliated with the Regional Center is compliant with EB-5 statutory and regulatory requirements, as well as binding EB-5 precedent. A common business structure is summarized in the chart below.

- Investment Offering Documents: Documentation of the capital investment offering documents must include, at a minimum, the following:

- A description and documentation of the business structure of both the regional center and the commercial enterprises that are or will be affiliated with the regional center, such as Articles of Incorporation, Certificate of Incorporation, or legal creation as a partnership or limited liability company (LLC), partnership or LLC agreements, etc.;

- Draft subscription agreements for investment into the commercial enterprise;

- Draft escrow agreements and instructions, if any;

- List of the proposed financial institutions that will serve as the Escrow Agent, if any;

- Draft of the offering letter, memorandum, private placement memorandum, or similar offering to be made in writing to an immigrant investor offering capital investments through the Regional Center; and

- Draft memorandum of understanding, interagency agreement, letter of intent, or similar agreement to be entered into with any other party, agency or organization to engage in activities on behalf of the Regional Center.

Regional Center Costs

A properly planned and managed Regional Center with a sustained project and investor pipeline can be completely self-funded, and may even generate a profitable revenue stream, using the fees charged to foreign investors. These fees, typically labeled “administrative fees” are in addition to the principal investment and may range from $35,000 to $65,000 per foreign investor. However, the majority of Regional Centers charge $40-45,000.

The costs associated with the set-up and management of a Regional Center vary depending primarily on the scope of the proposed project and the extent to which the Regional Center chooses to market. In addition to start-up costs listed below, first-year sales, operations, and marketing fees should be accounted for. However, in the case of Real Estate Investment and Development Firm, a lot of these costs could be defrayed by integrating Regional Center operations with the current Firm operations.

Start-up costs and expenses for developing a Regional Center are typically as follows:

- Economist Fees for: (1) construction and analysis of the econometric model; (2) development and drafting of the EB-5 Business Plan; and (3) development and drafting of the Regional Center Five Year Operating Plan and Budget—$25-55,000.00.

- Legal and Consulting Fees for: (1) transaction due diligence; (2) equity fund structuring; (3) EB-5 immigration law qualification; (4) securities law diligence and compliance; (5) representation before USCIS for project submission and approval; (6) individual investor preliminary qualification; (7) drafting application and transactional documents including (i) memorandum of terms, (ii) private placement memorandum, (iii) subscription agreement, (iv) partnership agreement, (v) escrow agreement; and (8) supervision and review of economic impact analysis, operational plan, and business plan to ensure USCIS compliance—$75,000 – $200,000.

- USCIS Governmental Filing Fees—$6,500.00.

An EB-5 funding model, if carefully planned and structured, could be an excellent and low-cost method of raising capital. The range of capital raised through EB-5 Regional Centers has individually varied anywhere from $5 Million, on the low end, to $300 Million, on high end. There has been increased awareness and interest by foreign investors in the EB-5 program, and it is forecasted that a record number of foreign investors will be issued EB-5 visas this year.

Although this is an overview of the process behind setting up a Regional Center, it is important to determine the exact scope of the proposed project to properly assess feasibility. The first step is to evaluate the underlying project or projects to ensure that they will not only be profitable, but will also meet USCIS requirements of the EB-5 program. Proper planning and careful due diligence by all parties involved is essential.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: These materials have been prepared by Wassem M. Amin, Esq. for informational purposes only and are not legal advice. The material posted on this web site is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship, and readers should not act upon it without seeking professional counsel.

Wassem M. Amin, Esq., MBA is an Associate Attorney at Dhar Law LLP in Boston, MA and is the Vice Chairman of the Middle East Division as well as the Islamic Finance Committee of the American Bar Association’s International Law Section. Wassem has extensive experience in the Middle East region, having worked as a consultant in the area for over 9 years. Wassem currently focuses his practice on Corporate Law and International Business Transactions. For more information, please visit the About Us page or request more information on our Contact Us page.